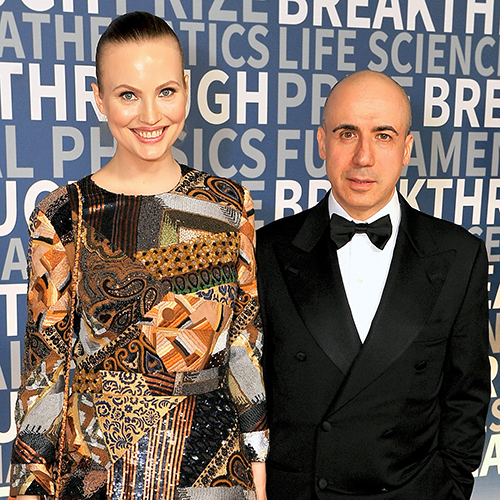

Yuri and Julia Milner

In creating the Giving Pledge, Warren Buffett and Bill and Melinda Gates have not just encouraged us to invest in problem-solving. They have also brought something approaching the scientific method to philanthropy. This means not just giving, but trying to learn from real-world experience and experiment in order to give effectively."

Pledge letter

My Giving Pledge

Yuri Milner

In 1894, Hermann Einstein lost the contract to supply electrical devices to the city of Munich. His company folded. As a result, his teenage son, Albert, had to rely on the support of relatives to fund his last few years of schooling.

A question for economists: What was the rate of return, for humankind, on that investment?

Well, it’s a hard question to answer: we don’t know whether Einstein could somehow have become a physicist without completing formal education, or if some other genius would have discovered his theories soon enough. More importantly, we don’t yet know all the implications of Einstein’s theories. If we look only at General Relativity, its practical applications are far from trifling: GPS alone has changed the world. But we are only beginning to explore the Universe beyond our provincial zone and scale. In years to come, Einstein’s insights into space, time, energy and matter could transform us in ways we cannot imagine.

When I was discovering science, men like Einstein and Galileo were my heroes: they had not just genius, but the courage and conviction to defy conventions. I followed my passion for theoretical physics, and went on to work as a doctoral student, investigating fundamental particle interactions. But eventually, I realized I was better at predicting the trajectory of firms than the trajectory of fermions. Since the late-nineties, I have been investing in technology companies around the world.

Recently, I have also been investing in scientists. In 2012, my foundation launched the first Fundamental Physics Prize, for major contributions to our understanding of the deep structure of the Universe. And this year, I joined Sergei Brin, Anne Wojcicki, Mark Zuckerberg and Art Levinson in developing the Life Sciences Breakthrough Prize. It rewards great discoveries in medicine, particularly molecular biology and genetics.

Because of this, I am sometimes described as ‘a venture capitalist turned philanthropist’. The implication is that the two are wildly different, even opposite, activities. But in fact, there is a job description broad enough to cover both: ‘investor’.

Both scientists and entrepreneurs ask questions about reality—the physical, biological and social worlds—and imagine solutions. An investor looks at the questions and the provisional answers, and makes judgment calls about their potential. Good judgments about tech firms tend to result in financial returns; and wise non-profit investment can also bring immense rewards. It’s not just that understanding the Universe and living organisms will profit us technologically; simply by fulfilling our human urge to know, these discoveries enrich us all.

In my opinion, scientific brilliance is currently under-capitalized. If the market dictates that a top banker can earn a thousand times more than a great scientist, then this is an area where philanthropy can make a world of difference—and so make a difference to the world. And along with financial capital comes cultural capital: why shouldn’t scientific superstars have the same power to inspire as their peers in art, media and sport? Some of the scientists who win our prizes are solitary dreamers. Others run big, dynamic labs. But all of them, in their different ways, are leaders.

I believe that progress comes quickest when individual leadership drives collaborative ventures. It is the creativity of extraordinary people that conjures truly new ideas; social networks apply them, extend them, fill in the gaps and nurture the next generation of geniuses.

In creating the Giving Pledge, Warren Buffett and Bill and Melinda Gates have not just encouraged us to invest in problem-solving. They have also brought something approaching the scientific method to philanthropy. This means not just giving, but trying to learn from real-world experience and experiment in order to give effectively. This is a sure sign of progress: we are finding more answers, and we are getting better at asking the right questions.

Because of the acceleration of progress, and the urgency of our current problems, it is tempting to regard the present as an end point, to which everything has been leading. In reality, we are at the very beginning of human history. We are only now beginning to escape the confines of our nature—to out-think our pathogens, outsource our memories, open-source our brains and link them together. We have no idea where our ideas can take us. But to find out, we must invest in them now.

The human adventure has barely begun. I am hereby joining Giving Pledge to invest in our leading minds and our shared future.